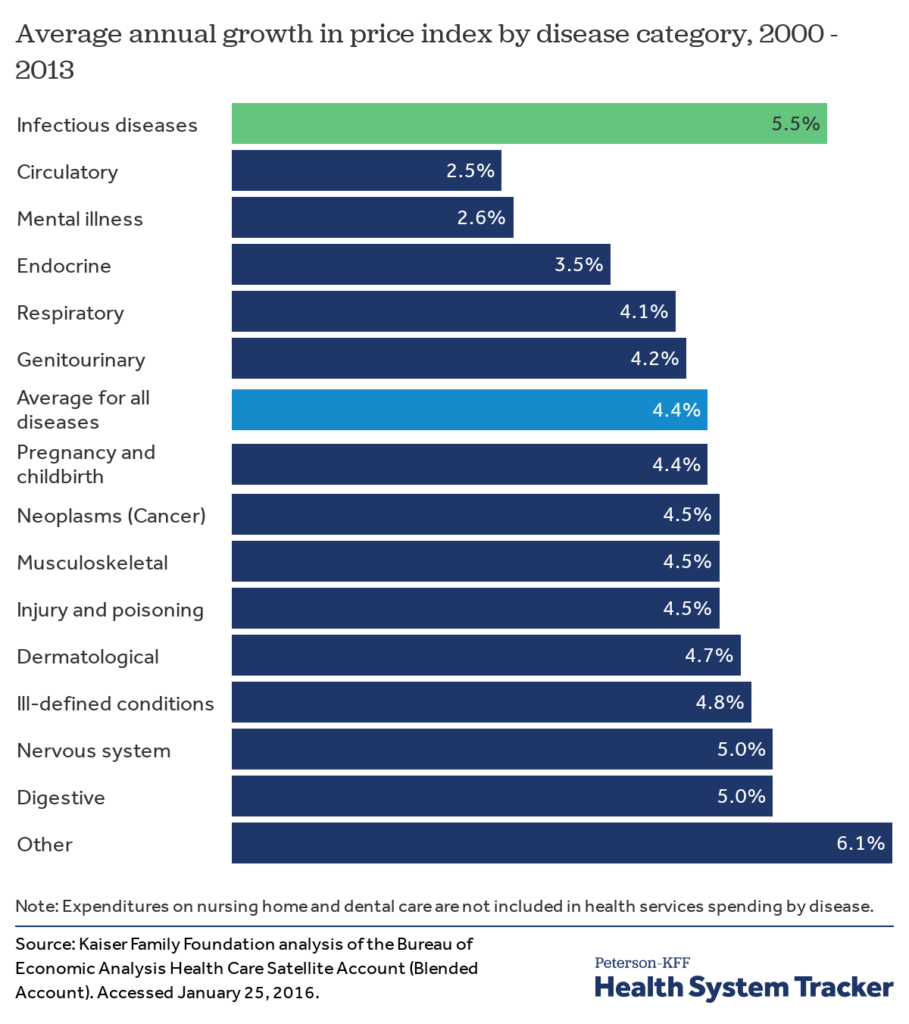

Antibiotics and focusing on infectious diseases is not the area where brainpower and money are focused on presently. It’s not as if people have suddenly stopped getting infections or that we don’t incur huge medical care costs because of them. Three infectious diseases were ranked in the top ten causes of death worldwide in 2016 by the World Health Organization. In the US, Among major disease categories, the cost per case grew fastest for infectious diseases.

Meanwhile the cost of treating patients who develop sepsis in the hospital rose by 20% in just three years, with hospitals spending $1.5 billion more last year than in 2015. In the US, the average cost per case for hospital-associated sepsis was slightly over $70,000 in 2018 with an annual increase in incidence of nearly 13%. Each year at least 1.7 million adults develop Sepsis and one in three patients who die in a hospital have Sepsis.

So, why the apparent lack of interest in tackling the problem? The challenges with new antibiotics development have been eloquently summarized by Isaac Stoner that I would highly recommend reading regardless of whether you are interested in this space or not. This captures the challenges faced by an antibiotic developer in achieving commercial success even if they have achieved technical success (i.e. a new antibiotic that works). Largely because of these struggles, many have concluded that antibiotics development carries too high a risk with very little return presently; one just has to wait until someone finds a way to make antibiotics profitable again.

Paradoxically, the situation, impact, and incentives work the other way for diagnostics. But this does not appear to have been fully appreciated by the broader audience yet. And recent “successes” have not delivered on expectations. But the case to persist is strong.

What is the case for diagnostics?

While the benefit and impact of new antibiotics is hard to quantify, what is clear is that we can improve patient outcomes, reduce cost of treatment, and slow spread of antimicrobial resistance by ensuring that we use existing antibiotics efficiently.

There are 270million antibiotic prescriptions filled in outpatient settings in the US each year while over half of all hospital patients receive antibiotics during their stay. Of these 23-51% of antibiotics were inappropriate or not associated with documented diagnosis. In other words, 50 – 130 million antibiotic prescriptions may not have been needed or would not have been appropriate.

New antibiotics struggle to achieve commercial success because they are reserved for use as a last resort. This antibiotic stewardship, which is needed, limits the number of prescriptions for the new antibiotic making it difficult to achieve profitability. Having a diagnostic determine which antibiotic to administer (new or existing) promotes stewardship and reduces both overuse and misuse of antibiotics. If done right, the volumes of these tests would be sufficiently large (100 million tests in US alone each year) to assure profitability.

Diagnosis-related Group coding (DRG; where insurers pay a lump sum to hospitals for treatment) incentivizes hospitals to use inexpensive antibiotics, which places significant pricing pressure on new expensive antibiotics. But, it also incentivizes hospitals to get the initial antibiotic right since use of appropriate antibiotics early improves patient outcomes and reduces length of stay. i.e. hospitals get to keep more of the lump sum payment increasing their profit margins. In cases like Sepsis (which is one of the most expensive conditions to treat in hospitals), this makes a huge impact. It may even be the difference between whether the hospital is able to break even or not.

So, a well-designed diagnostic approach will garner strong stakeholder (patients, payers, society) support and command large volumes needed to be successful. It is difficult for antibiotics, with the healthcare and reimbursement models in effect today, to have such support or volumes.

Challenges

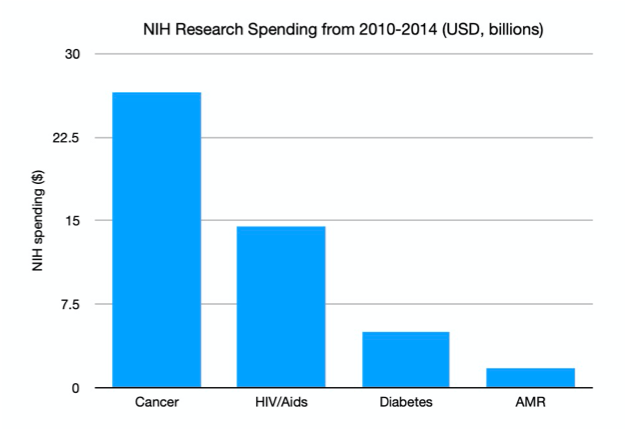

The one area where antibiotic development and diagnostics development share common ground is in investment attention – both struggle for it. Even well-intentioned programs like CARB-X and NIH grants do not devote sufficient funds for diagnostics development (see chart). While several governments, notably the UK, and the WHO have been campaigning for greater investment action, there are no moonshot initiatives to combat antimicrobial resistance. All this despite evidence that an appropriate diagnostic would allow us to dramatically improve the efficiency of existing drugs and buy us time to develop other long-term strategies.

Even though the market is huge, the impact is huge, and there is a real problem in need of a solution, limited resources (human and financial) have been devoted to this area and problem. So, we find ourselves in the situation today where there is no diagnostic that can help physicians determine if an antibiotic is necessary and which one to use. The core technology we use is effectively the same since the early 20th century!

This is partly because the approaches being attempted use the same basic strategy as those that have been tried before (that did not yield desired outcomes) with advances in technology incorporated. so, it is not too surprising that they have not yielded the desired results. The willingness to adopt a high-risk high reward strategy by investors as done in areas such as oncology therapeutics has been conspicuously absent. It’s not that investors are not aware of the challenges posed by AMR and Sepsis or the need for a solution. But, there needs to beat least one good commercial success story to renew the interest in this space. The high rewards are not readily apparent to investors burned by previous approaches. New, improved technical solutions and business models have not matured/been developed either. And this paucity of solutions is only made more difficult as talent seeks the security of better-funded areas.

They have been proposals to increase the economic incentives for developing much needed antibiotics. So far these well intentioned efforts have not resulted in some technical success but not the growth of self-sustaining companies. Pragmatically the success story is more likely to come via diagnostics (for the reasons outlined above) than in therapeutics. Or through a combination of diagnostic and therapeutic approaches enabling precision medicine for infectious diseases.

Progress

Despite these challenges, we are optimistic about the prospect of new innovative solutions and our platform, Biospectrix™. The ideal diagnostic should be able to detect the presence/absence of bacteria, determine its identity, and if it is antibiotic resistant – all in 15-60 minutes. Early results in our lab indicate that we can meet all of the above requirements.

With our approach, we aim to isolate, detect, and identify bacteria in < 1 hour without destroying the bacteria. The information from the analysis is utilized by the physician to administer the appropriate antibiotic. Through this process, patient outcomes will improve, length of stay in hospitals will decrease, hospital profit margins will improve, and, crucially, we can slow down the spread of antimicrobial resistance by cutting down on inappropriate antibiotic use. This is an outcome worth persevering for.

And, by the way, once we are done with our analysis, the bacteria can be cultured (from the sample we analyzed) and subjected to further analysis, if needed, but without the time pressure.

Enabling targeted therapy will permit new antibiotics being used judiciously as opposed to simply being saved as a method of last resort when it might be too late. Judicious use would provide the volumes needed for antibiotic developers to be profitable. It would also prolong the life of existing drugs. The possibilities for individual and societal good and commercial success are tantalizing. And that is why we believe that diagnostics are the place to start to combat AMR and Sepsis.

There is still some ways to go and many challenges to overcome before this vision becomes reality. But, we do so knowing that technical and commercial success with a positive impact on patients and healthcare, as we know it, is near. Jim O’Neil stated in his assessment on antimicrobial resistance, “One of the greatest worries about AMR is that modern health systems and treatments that rely heavily on antibiotics could be severely undermined.” We intend to do our part in preventing this bleak scenario from becoming reality.